Children need to know, and to see in books, the truth — the beauty, intelligence, courage, and ingenuity of African and African American people. Eloise Greenfield, CSK Virginia Hamilton Lifetime Achievement Award Acceptance Speech

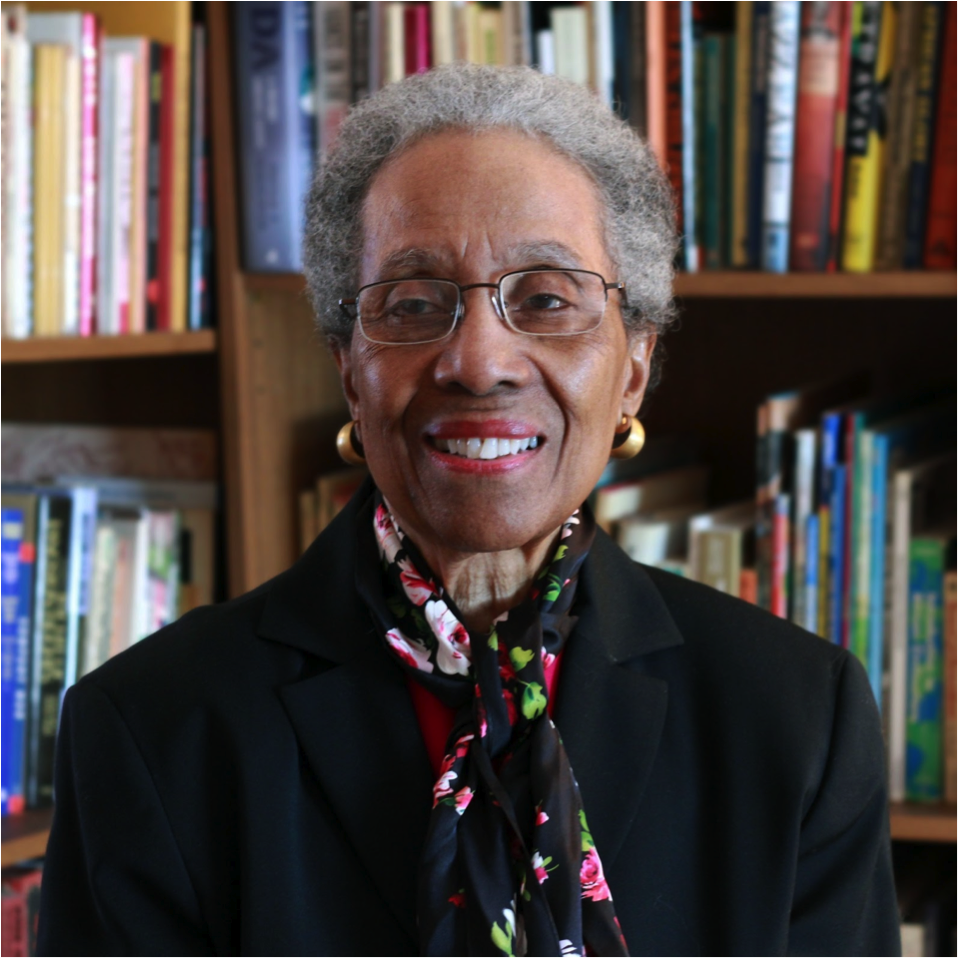

CSK Legends is a series of interviews saluting early recipients of the Coretta Scott King Book Award. For our first post in this series we raise the spotlight on Eloise Greenfield.

With a career spanning over fifty years and nearly as many books to her credit, Eloise Greenfield is one of the most beloved authors of children’s literature.

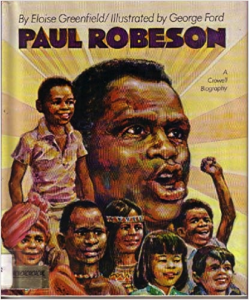

With work that spans a range of genres, including poetry and informative prose, Greenfield won her first Coretta Scott King Honor for her biography Paul Robeson in 1976. In 1978 she received the CSK Author Award for Africa Dream and a CSK Author Honor for her biography of Mary McLeod Bethune. She subsequently won CSK Author Honors for Childtimes: A Three Generation Memoir (1980), Nathaniel Talking (1990), Night on Neighborhood Street (1992) and The Great Migration: Journey to the North (2012).

The following interview took place over several email exchanges and has been edited for clarity. …………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Jené Watson: What an honor to interview you! Congratulations on being the 2018 recipient of Virginia Hamilton Award for Lifetime Achievement.

Eloise Greenfield: It is my honor to have received such a special award.

JW: You originally planned to be a teacher, then worked in civil service for a while before (or at the same time that) you began writing in earnest. What made you decide to focus your attention on writing exclusively for children?

EG: My shyness interfered with my plan to become a teacher, and after I had worked for a while in the 1950s as a civil service clerk-typist, I became bored. I had always loved books and words, and I felt that I could become a writer, one who was reclusive, as some writers are.

Throughout the 1950s, I studied books on the craft of writing and submitted my poems, stories and articles to publishers. After many rejections, I finally had a poem published in 1962, and throughout the sixties my poems and short stories for children and adults were published in Scholastic Scope and in Negro Digest.

In 1971, I headed the adult fiction division of the D.C. Black Writers’ Workshop, founded and directed by Annie Crittenden. I had written Bubbles, which later became my first children’s book, and Sharon Bell Mathis, who headed the children’s literature division, suggested that I write a picture book biography for the Crowell Publishers series, now a part of HarperCollins. Subsequently, I continued to write for children.

JW: Songs are the stories that children are first introduced to, and in some cases songs and poetry are one and the same. Two of my favorite things about your work are its everyday poetic language and your commitment to offering more rounded views of black children, families and communities. Please talk about why this is so important.

EG: I feel that poetic language is not restricted to formal speech. We can hear in all kinds of language the in-depth meanings and the musicality that make it poetic. I want children to know this, to hear the power of language and also to know how beautiful and intelligent African and African American people are.

On the other hand, writing is never fun for me. It’s work, because I have to concentrate on the craft I have studied and keep revising until all aspects — the meanings and the musicality of language — are exactly what I want them to be. No, writing is not fun, but it’s satisfying work, and I love every minute of it!

JW: You won your first CSK Honor in 1976 for your biography Paul Robeson. A little before that, in 1973, you wrote a similar biography on Rosa Parks  and in 1977 you devoted one to the life of educator Mary McLeod Bethune. How did you select the subjects for your biographies? Did you choose the subjects to write about or did a publisher suggest them to you?

and in 1977 you devoted one to the life of educator Mary McLeod Bethune. How did you select the subjects for your biographies? Did you choose the subjects to write about or did a publisher suggest them to you?

EG: These biographies are all a part of the Crowell Biography Series. I chose them because I didn’t feel that enough had been said about them and the importance of their work.

JW: What effect did winning your first CSK have on how you thought about your writing? What kinds of shifts did you notice in your career after winning it?

EG: Awards have not changed the way I feel about my writing. I feel that it’s important that writers take seriously their efforts and the effect they have on the public and always to do their best work. Awards bring attention to an author’s work and often an increase in sales, and are wonderful pats on the back to let us know that our work is appreciated.

JW: Some critics insist that the world has moved beyond the need for ethnically-based awards and that awards like the CSK are not as relevant or necessary as they once were. As an elder who’s witnessed trends and cycles, can you speak to this? And how would you compare the present terrain of publishing for children of color to that of past decades?

EG: Although there have been improvements in the number and quality of good books about African and African American people, these awards are as important as they ever were. Racism still exists in life and in literature, and even if racial discrimination were to end, the awards would take their place among all the other awards that exist in literature and in so many other fields.

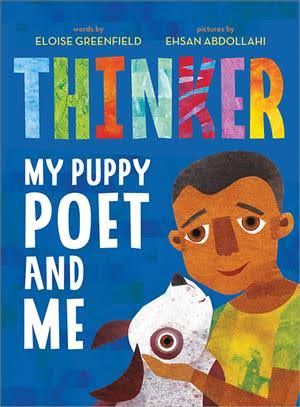

JW: You’re keeping busy with fun projects where you’re collaborating with younger artists. One of them is a lively Youtube video of you doing “Nathaniel’s Rap,” filmed and produced by your grandson, Terique Greenfield. The other is a gorgeous picture book about a boy and his dog titled Thinker: My Puppy Poet and Me illustrated by Iranian artist, Ehsan Abdollahi. How did these projects come about?

EG: The “Nathaniel’s Rap” video was produced several years ago. [It’s a] poem from my book Nathaniel Talking. My grandson, Terique Greenfield, who is a composer and also has sometimes directed videos, wrote the music and directed the video for me. It turned out very well, and it was fun, because I had no creative responsibility. I just had to follow Terique’s directions.

About two years ago, I was followed on Twitter by Tiny Owl Publishing, a company in Britain. I followed them back. I then sent the manuscript for Thinker. They loved it and engaged Ehsan Abdollahi, a highly regarded artist, to illustrate it. The book was published in April 2018, and has received many favorable reviews. The British edition of Thinker contains a few British spellings, and I am happy that an edition with U.S. spellings will be published in the U.S., in April 2019, by Sourcebooks Jabberwocky.

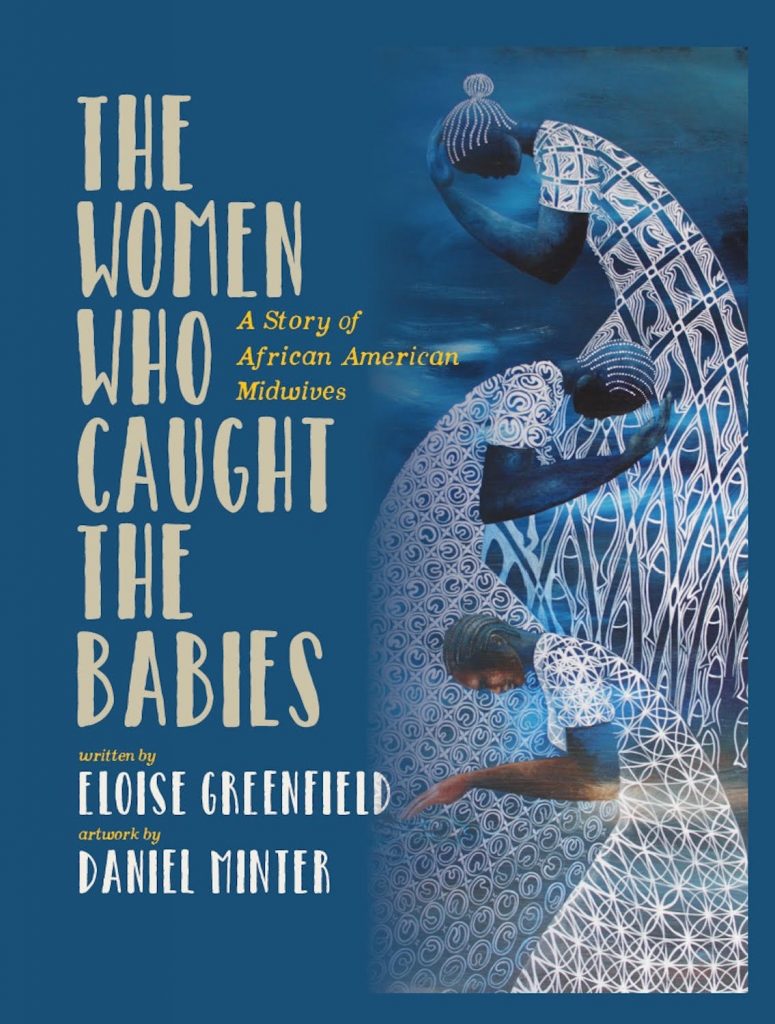

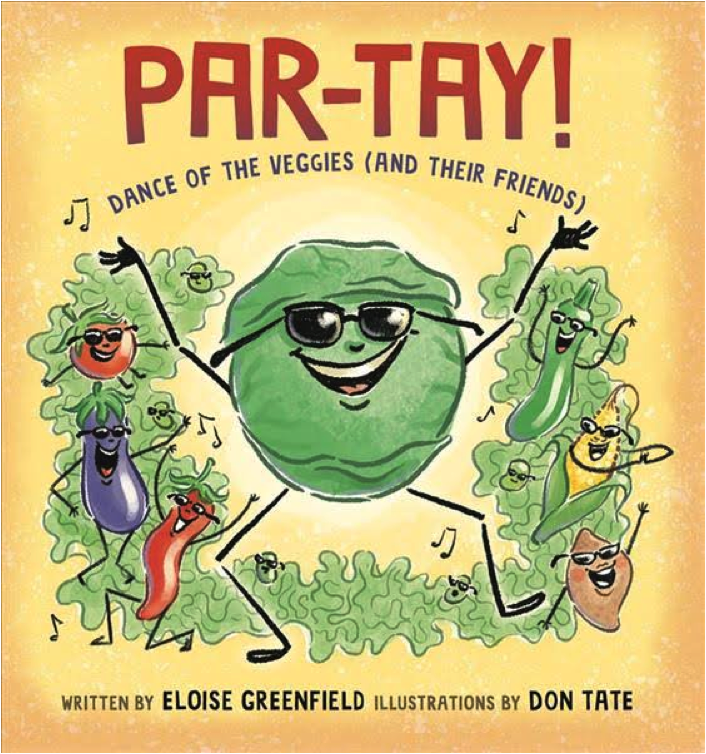

Two other acclaimed artists have recently illustrated my books: Don Tate, PAR-TAY!: Dance of the Veggies and Their Friends (2018) and Daniel Minter, The Women Who Caught the Babies: A Story of African American Midwives (2019), both by Alazar Press.

JW: Many of your earlier books are still in print after more than 40 years. To what to you credit your literary longevity?

EG: I credit the longevity of some books to many factors. In addition to the quality of the text and illustrations, there is the subject matter and the tastes of the reading public, the work of the agents and publicists, marketing by the publisher and booksellers, as well as the awards and favorable reviews that bring attention to the work.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Follow Eloise Greenfield on Twitter @ELGreenfield

Jené Watson is a writer, mother and public librarian who lives in suburban Atlanta. She loves arts and history and is the author of The Spirit That Dreams: Conversations with Women Artists of Color (indigopen.com).