Family history has always fascinated me. Like the elders of many African American families, mine migrated from backwater Southern towns to a more thriving one in the 1930’s. Their personal histories were, however, closed doors. Fortunately, encountering Mildred D. Taylor’s Roll of Thunder Hear My Cry and Let the Circle Be Unbroken in elementary school gave me keys to understanding. Once this access was granted, I could feel and imagine the worlds of my grandparents and their predecessors– comforts and terrors alike.

Like the West African griots of long ago who passed down family histories, Taylor has devoted most of her literary career to telling one story: that of the Logans, a proud black family of the Southern United States. Her stories are to children’s literature what Alex Haley’s Roots is to adult historical fiction. Both make history dance and command our attention, awakening ancestral memory in a way that cold facts and timelines cannot.

Special thanks to Janell Walden Agyeman of Marie Brown Associates and Regina Hayes of Penguin Random House for helping to arrange this exchange which happened by email in Spring 2019. It has been lightly edited for posting on this blog.

~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*

JW: First, thank you for agreeing to this interview. After Song of the Trees was published in 1975, did you have any idea that you would continue to share parts of Cassie’s family story for the next forty years? Also, you’re putting the finishing touches on the final installment which you’ve titled All the Days Past, All the Days to Come. How does it feel drawing the Logan family saga to a close?

MDT: I had planned from the very beginning to tell Cassie’s family story, although I didn’t have any idea how long it would take. I have felt such an obligation to finish the story; it has pressed on me. At one point I even gave back the contract advance for the final book, feeling the pressure was too much. But I had made a commitment, and I wanted to finish the Logan story. It saddens me that this book is the end, but there is also a sense of relief. I am done!

JW: Along with the inspiration that you got from your family, specifically your father, what published writers influenced your storytelling?

MDT: It may surprise you to learn that the writer who influenced me the most was Harper Lee. I loved Scout of To Kill A Mockingbird. My Cassie Logan had a different story to tell, from a Black point of view.

JW: Your work foregrounds the dignity and self-respect of the Logan family in the face of the indignities of the Jim Crow era. In every instance, your stories move beyond struggle and woe to emphasize courage, the power of family unity. I also love how nature plays an important role in all of the Logan stories that I’ve read. Do you intentionally place courage and reverence for nature at the heart of your work?

MDT: Yes, both courage and reverence for nature. I was born in Mississippi but left when I was three months old, and although I grew up in Toledo, my family went yearly–sometimes even twice a year— back home to Mississippi, to the land. It was beautiful, with forests and ponds and we would walk it drinking in the beauty and appreciating the calm and peace of the trees and the land our family had struggled to obtain and hold onto. This was land my great-grandparents had bought after they came from slavery. When I saw the land where I now live in Colorado, it spoke to me in the same way.

JW: After winning your first literary awards, namely the CSK, what changes happened in your career? And did this kind of recognition have any effect-on how you approached your writing?

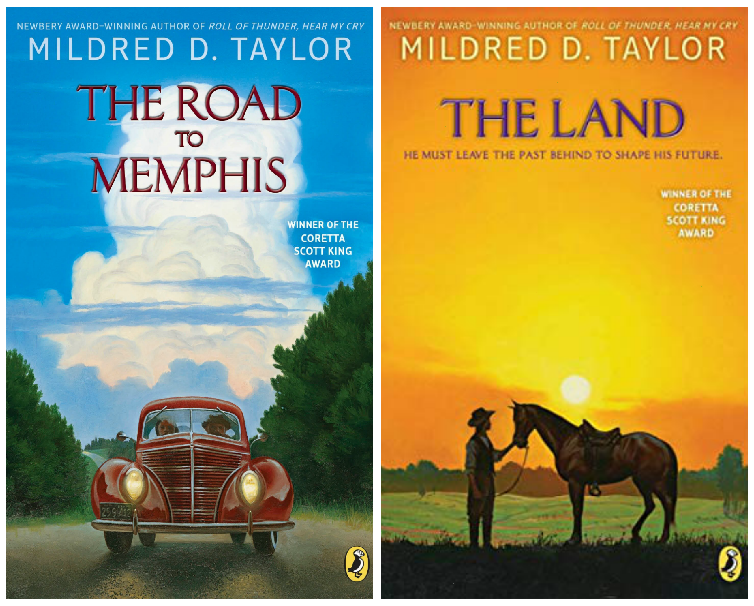

MDT: Well, actually, my first literary award was winning the contest sponsored by The Council on Interracial Books for Children, and that led to the publication of Song of the Trees. My second literary award was the Newbery Medal, for Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry. So in a sense, big changes had already occurred. But of course it was wonderful to win the Coretta Scott King award for four of my books. I have never liked making speeches. Preparing speeches and delivering them drained and distracted me from my work; therefore, I have seldom attended award ceremonies. When The Road to Memphis won the award, I was actually on the dais with Mrs. Rosa Parks and was able to talk with her. My greatest regret concerning the award is when I was unable to attend the ceremony to accept the Coretta Scott King award for The Land, and I missed the chance to receive the award from Mrs. King herself.

JW: Before becoming an established writer, I read that you taught on both a Navajo reservation in Arizona and in Ethiopia. These cultures have strong poetry and verbal storytelling traditions. How, if at all, did these experiences influence your own storytelling?

MDT: I spent three weeks on the Navajo reservation in preparation for teaching with the Peace Corps in Ethiopia. There were only white teachers on the reservation and the children crowded around me since my skin was brown like theirs. One little boy in particular was so sweet to me; he put his arm next to mine and said, “Look, Miss, we’re alike!” I had similar experiences in Ethiopia, where the people I met had never seen an African American.

Although both Navajo and Ethiopian cultures have a storytelling tradition, my own storytelling grew entirely out of the Southern tradition [of the U.S]. We were a family of storytellers. Whenever the family was together, we loved hearing and telling the stories of past events.

JW: From your perspective as a literary veteran and culture keeper, what value do you think that awards like the CSK have? Are they still as important as they once were? And how would you compare what’s being published today for children of color to that of past decades?

MDT: I am not in a position to evaluate this. When I am writing, I don’t read other writers’ work, and I’m usually quite unaware of the awards and their impact. One trend I deplore is the pressure to whitewash the past. The past was not pretty – I lived it and I remember and I am determined to portray it as it was.

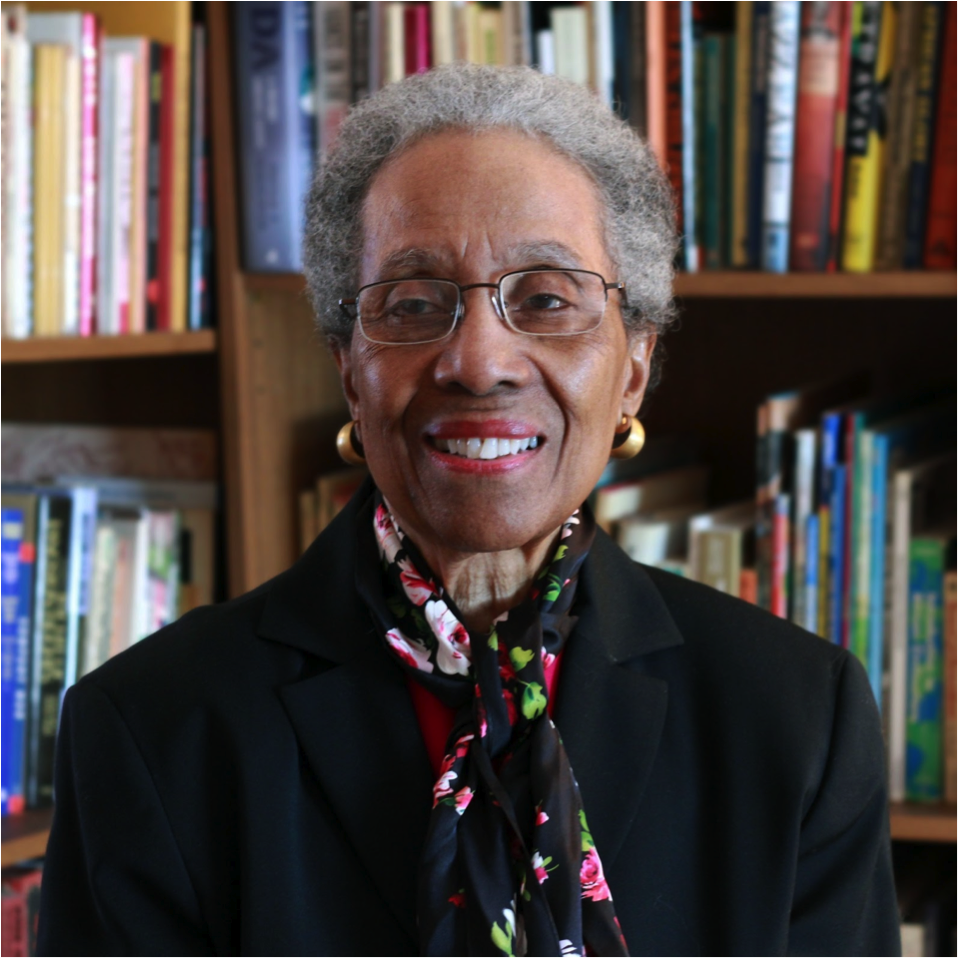

Mildred D. Taylor has won the Coretta Scott King Author Award for The Land (2002), The Road to Memphis (1991), The Friendship (1988) and Let the Circle Be Unbroken (1982). She is also a two-time recipient of the Coretta Scott King Author Honor for Roll of Thunder Hear My Cry (1977) and Song of the Trees (1976).

Jené Watson is Chair of the CSK Technology Committee as well as a mother, writer, educator and librarian who lives and works in suburban Atlanta. She is the author of The Spirit That Dreams: Conversations with Women Artists of Color.

and in 1977 you devoted one to the life of educator Mary McLeod Bethune. How did you select the subjects for your biographies? Did you choose the subjects to write about or did a publisher suggest them to you?

and in 1977 you devoted one to the life of educator Mary McLeod Bethune. How did you select the subjects for your biographies? Did you choose the subjects to write about or did a publisher suggest them to you?